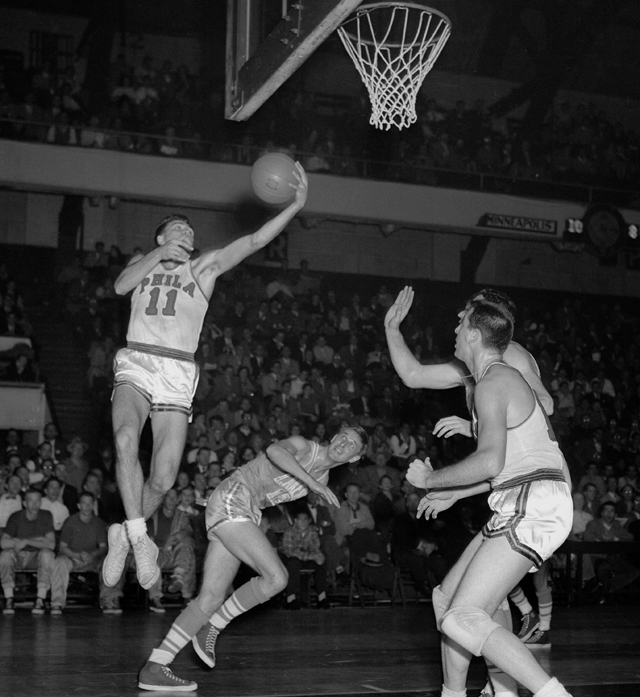

Ask people who saw Paul Arizin play about the forward’s game, and they will always mention the jump shot. He was one of the first to leave his feet while shooting, and that helped him score plenty while at Villanova and later with the Philadelphia Warriors.

Not long after that, talk will turn to the wheeze. It was a horrible sound, and when Arizin ran up and down the court, he sounded as if the next step would send him straight to the graveyard. Some NBA greats have glided across the hardwood, seemingly never touching the ground. Arizin sounded like a dump truck stuck in first gear. If Yankees great Lou Gehrig was the “Iron Horse,” Arizin should have been called the “Iron Lung.” Many thought he suffered from asthma, but the real problem was a sinus condition that had begun when he was young. At least that’s what Arizin told anybody who asked. “It never hurt my endurance,” he said. Nope, it just hurt people’s ears.

“Everybody thought he was dying,” says Ernie Beck, a standout at Penn and a teammate of Arizin’s for six years with the Warriors. “He would be breathing heavy all the time, and people thought he was tired. I would practice against him, and I would say, ‘Paul, you’re a fake. You’re just trying to set me up.’”

Opponents couldn’t imagine that it didn’t affect him. The up-tempo Celtics always figured they had an advantage over Philadelphia, because their fastbreaking style would eventually send Arizin wheezing to the bench, or better yet, an oxygen tent.

“It was always amazing to me that he could finish a game,” former Celtic forward Tom Heinsohn says.

The grunts, gasps, coughs and rattle never stopped Arizin. Most opponents couldn’t, either. The Hall of Famer reached the All-Star Game in each of his 10 seasons in the League. He averaged 22.8 ppg for his career and was a trailblazer in a game that had been dominated by set shooters and earth-bound performers. It was nothing to see Arizin pull up from 20 on the break and send that line-drive J of his through the hoop. Sounds like he would have been perfect for today’s game.

“He was part of the pioneer phase of the NBA,” Heinsohn says.

That’s for certain. Try to imagine someone in the League today who never played high school ball and after being discovered by his college coach playing in dance halls and church leagues eventually becoming the national college Player of the Year. How’s that for the Old Days? Try to imagine the recruiting sleuths today overlooking a talent like Arizin or big-time coaches not showering him and his people with affection.

That’s as unreasonable as the idea of an All-Star’s quitting to play in the minors because his franchise moved to another city. That’s what Arizin did in 1962, when the Warriors went west to San Francisco. He wasn’t interested in playing anywhere but Philadelphia, and the Golden State didn’t excite him. So, he took a real job and spent three years in the Eastern League, providing further credence to the fact that he played the game because he loved it.

“Paul came to play, did his job and went home,” says Al Attles, who played two of his 11 NBA seasons with Arizin in Philadelphia. “The thing that impressed me as a young kid coming out of college was that he would come to practice and then go home to his family.

“He taught me what the NBA was all about. Work hard and come prepared to do your job.”

That was Arizin. He was a Philly guy. He was born there, played ball there and he died there, in 2006.

Arizin was also a pure scorer, whose jump shot confounded defenders and whose rocking, jab step move created space for him to squeeze the trigger over taller opponents. Arizin was relentless on the court but amiable and generous off it. He may have sounded on the court like the wreck of the Old 97, but he was first class off it.

“Paul was one of the most honest guys I ever met,” says Tom Meschery, who spent his rookie season—Arizin’s last—with the Warriors. “He was completely without guile and was a great, straightforward guy.

“But he was one of the best offensive players of all time.”

***

The hoop was a coat hanger, and the ball was a wad of socks. Sonny Hill would retreat to his bedroom on the third floor of his grandmother’s Philadelphia house and transform himself into Paul Arizin. Make that “Number 11, Paul Arizin,” as Hill always said while providing the play-by-play soundtrack for his imaginary games.

“Paul’s game was a transitional game,” says Hill, himself an excellent player who is an advisor to the 76ers and former TV analyst on CBS’ NBA telecasts. “He could have played in the modern game. He had that kind of skill and played like they do now.”

Hill was a standout prep player who spent two years in college before joining the Eastern League in the late ’50s. The NBA had only eight franchises at the time, and the unspoken quota of two African-American players per team meant those Eastern squads had some pretty good talent. In 1962, the Camden Bullets added Arizin, who had scored 21.9 ppg the year before with the Warriors. Suddenly, Hill was playing with his hero, the man he idolized and after whose jump shot he patterned his own.

“What a thrill,” Hill says. “Imagine that Paul Arizin passed you the ball. And then, he told you to shoot the ball.”

Arizin didn’t set out to change the game. In fact, his jumper was developed out of necessity, instead of some burst of athletic creativity. Because he was cut as a senior from his team at La Salle HS, Arizin found himself scrambling for the opportunity to play. He joined teams in church and independent leagues and ended up playing on courts that weren’t quite regulation. Some were dance floors that were so slippery Arizin would lose his balance when he tried to plant for a hook shot. So, he jumped. Pretty soon, he was shooting nothing but jumpers, at a time when the hook and push shots dominated basketball.

But he was doing it against neighborhood guys and servicemen returning from the war. During the day, he studied chemistry at Villanova, whose coach, Al Severance, knew nothing about him. Upon seeing Arizin in a rec league, Severance offered him a shot to play for the Wildcats, a decision that resulted in Arizin’s joining the college ranks.

Venerable Associated Press basketball writer Jack Scheuer calls Arizin “Villanova’s best player,” quite a statement given the school’s long basketball history. But Scheuer is right: Arizin averaged 20.0 ppg for his career, including 25.3 a contest as a senior, when he was a consensus First-Team All-American and named National Player of the Year by Sporting News. In a 1949 NCAA Tourney game against Kentucky, Arizin poured in 30 to match UK standout Alex Groza.

In those days, the NBA granted its franchises territorial picks, the better to let them cash in on the popularity of local players. That meant Philadelphia had the rights to Arizin. (It’s how the Warriors ended up with Wilt Chamberlain, too.) After a solid rookie season (17.2 ppg) in 1950-51, Arizin led the NBA in scoring the following year with 25.4 ppg and also grabbed 11.3 rpg. Only legendary Lakers big man George Mikan and the Warriors’ Joe Fulks had ever scored more per game.

Arizin may have been able to flummox opposing defenders, but he couldn’t overcome the US Marine Corps, which drafted him into service during the Korean War. After his two-year stint, Arizin returned to the NBA as if he hadn’t missed a minute of play. After registering 21.0 ppg in 1954-55, he scored 24.2 a night the following year and led the Warriors to the League’s best record. In the Playoffs, Arizin was a fireball, pouring in 28.9 ppg a night and helping Philadelphia to its second-ever Championship.

Arizin could score, but he wasn’t merely a gunner. He pulled down 8.6 boards a game during his career and never shied away from the rough stuff. Though 6-4, he didn’t mind defensive assignments inside and wasn’t afraid of contact, as some shooters were.

“He did whatever was needed on the floor,” Hill says. “Paul was a competitor.”

That meant he would square off against players like Fort Wayne bruiser Mel Hutchins, 7-footer Walter Dukes of Detroit, and of course, Boston’s “Jungle” Jim Loscutoff, a 6-5, 220-pound ball of muscle for whom finesse was an alien concept. “Loscutoff used to work on him, but Paul was a strong guy,” Beck says. “If he got knocked down, he got right up.”

Beck roomed on the road with Arizin during their time with the Warriors and reports that the first thing his friend did upon arriving in a new town was seek out the Catholic church nearest to their hotel and learn the Mass schedule. “He kept me on the straight and narrow,” says Beck, who accompanied Arizin to church.

It’s hard to find someone who wasn’t impressed with Arizin’s character. OK, so he was a little frugal, but he was generous with his time and advice. Attles remembers joining Philadelphia in 1960 and trying to figure out how the pros handled themselves. He had no better example than Arizin.

“When you came out of college, where you went to classes all the time, and all of a sudden, you were living on the road, you needed role models,” Attles says. “Paul was one of them. When a guy was older, and a young guy comes in and sees him coming to work every day, that helps.”

Arizin led the League in scoring again in ’56-57, with 25.6 a game. Two years later, he averaged a career-high 26.4 ppg. But while Arizin continued to accumulate points and All-Star recognition, the Warriors couldn’t get past Boston in the Eastern Conference hierarchy. Even when Wilt joined the team in 1959 and was part of a contingent of legendary Philadelphia products that included Arizin, Tom Gola, Guy Rodgers and Beck, the Warriors were unable to supplant the Celtics, who functioned as a remarkable unit.

“Needless to say, we knew each other pretty well,” Heinsohn says of Philadelphia and Boston. “We had six set plays, and everybody in the League knew we had six set plays. But we were like the old Green Bay Packers and their sweep. Execution counts. We had so many counter moves off the plays, so people never knew what we would do.”

The 1962 Eastern Conference final matchup between Boston and Philadelphia was a seven-game classic that was decided in the final seconds of a two-point Celtic win. Afterward, Attles reports there was some grousing in the Warriors’ locker room about a controversial referee’s call at game’s end. Arizin put an immediate end to the complaining.

“He stood up and said, ‘We just were not good enough,’” Attles says. “That put a lid on it. That was Paul Arizin.”

After that season, Warriors owner Eddie Gottlieb sold the team and moved it to California, two years after the Lakers had migrated there from Minneapolis. Arizin didn’t like that too much and decided he would rather retire than head west, despite averaging 21.9 ppg in ’61-62. “He had three more years in his career,” Hill says. Arizin also had a house at the Jersey shore, a family that would eventually include four children and a new job with IBM as a sales manager.

“It wasn’t like it is now, where if you play one more year, you can retire forever,” says Heinsohn, who built a successful life insurance business while playing. “Everybody had to do something else.”

So, Arizin went to work for IBM and played with the Camden Bullets in the Eastern League, a 10-time All-Star in the semi-pro ranks. But he loved his family and his city, just as he adored the game. It’s hard to imagine one of today’s stars following the same path, but pro basketball in the early ‘60s barely resembled its 21st century counterpart. Arizin, however, would have been quite recognizable today, thanks to his athletic ability, his jump shot and all-around offensive game.

No matter how it all sounded.

Michael Bradley is a Senior Writer at SLAM. Follow him on Twitter @DailyHombre.