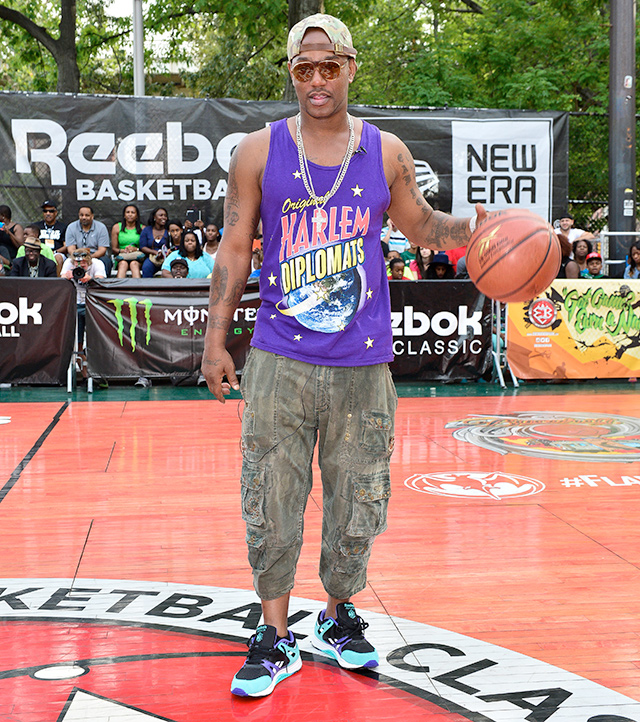

Cameron Giles, once one of the best high school basketball players in New York City, is showered with love as he walks through Rucker Park during a hot late-summer day in August of 2014. When former hoops stars return to the courts for events like this—a Reebok-sponsored high school all-star game featuring some of the best young talent in the city—they’re generally embraced warmly, with daps and hugs thrown in their direction by everyone from local legends to up-and-comers with a respectable knowledge of roundball history.

Yet when Giles saunters through the park, it’s not just a select few who show respect—everyone loses their shit. That’s because this Harlem native isn’t merely a former hoops prodigy; these days, Giles is known as Cam’ron, a platinum rapper with a bevy of hit singles, high-charting albums and an incredibly popular group to his name.

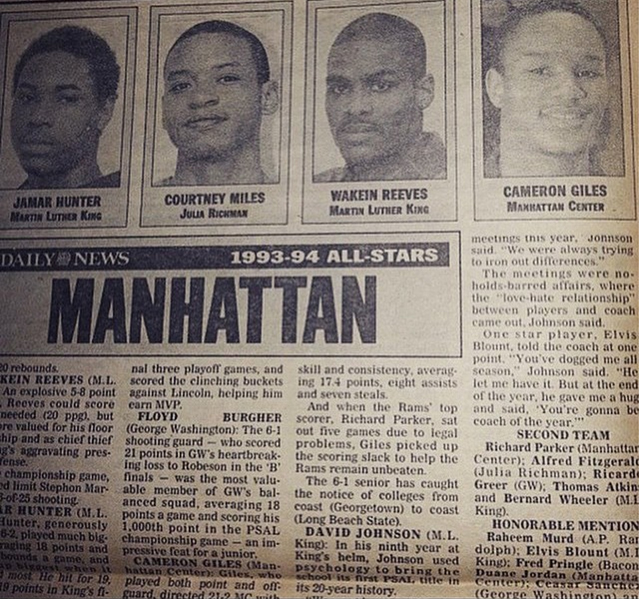

Despite his rap success, Cam’s earliest goals were your pretty standard hoop dreams. He grew up around 140th Street and Lennox Ave in Manhattan (where Nicky Barnes got rich as fuck)—coming of age in the same building as future NBA player God Shammgod—in a neighborhood littered with basketball courts, eventually attending Manhattan Center for Science and Mathematics in East Harlem. He famously played on the same high school team as Mason Betha—later known as the rapper Ma$e—and as sophomores in 1992, the two, along with Richie Parker (who would later lose a scholarship to Seton Hall because of a sexual assault charge), brought the team all the way to the Public Schools Athletic Class A championship at Madison Square Garden, defeating Stephon Marbury’s Lincoln squad to get there.

Unfortunately, Cam bricked a running three-pointer at the buzzer that would’ve given his team the victory, and Manhattan Center fell 55-53.

In Cam’ron’s self-produced, semi-autobiographical movie Killa Season, that miss is portrayed as the shot that changed everything; after it rims out, Cam turns to a life of drug-related crime and violence. In reality, however, he kept on hooping for both Riverside Church and The Gauchos—two elite AAU teams—and in high school, where as a senior, Parker and him achieved a perfect 25-0 regular season at Manhattan Center. Yet again, postseason success eluded them, and they lost in the first round of the playoffs.

“That team was dope,” Cam says. “[But] our 2-guard had gotten hurt. We went 25-0 and lost in the first round of the playoffs. Devastating.”

Cam’ron claims to have been recruited by Miami, Georgetown, Syracuse (“Jim Boeheim, he called me up and sent me letters, sent recruiters to the games,” he says, “though there were certain rules, like you can’t talk to them or whatever”), and Cam’s own mother has provided proof that some top-level programs had interest in her son:

That demoralizing first-round loss hit hard, though, and before his senior year even ended, Cam bolted the city. “My girl at that time, which is my son’s mother now, was going to college in Albany, and as soon as school was over I broke out and bought two ounces to start pitching up in Albany,” he said back in 2011 on the Juan Epstein podcast. “I just never went back to school—that was it.”

(On that podcast, Cam also referenced being ranked a Top 25 All-American—a claim he’s made elsewhere, and which, as Grantland has pointed out, was once discussed in a thoroughly entertaining NBADraft.net message board thread.)

Cam wound up earning his GED, then receiving an offer to play for Navarro Junior College in Corsicana, TX. That plan was derailed when he tore his hamstring at the onset of his NCAA career—then got kicked out of school following a weapons arrest—so he quickly returned to New York City, where drug (and later music) dollars were readily available.

“To keep it 100,” he says, “when I got back from school, and [Ma$e] had signed on with Bad Boy, I was like, I gotta get paid today. It wasn’t like I was in a D1—I would’ve had to go to junior college, then a D1, then hopefully the NBA. But there was money available for me right now.”

And with the exception of an infamous celebrity game appearance (see the video below), that was mostly it for Killa’s basketball pursuit. Cam would of course proceed to reach rap superstardom, later using that very platform to speak on his hoops journey. Here, via Rap Genius (with some grammatical errors cleaned up), are lyrics from his 2000 song “Sports, Drugs & Entertainment”:

After all, I was nice in ball

But I came to practice weed scented

Report card like the speed limit

55-55, expellable

If you’re nice, they make sure that you eligible

Pretty final, ’92 played the city finals

Pretty swift, real MVP at 55th

I can hoop, yo

All-American in my age group, yo

Raised bad, settled for a JuCo

Uh, but why they let a thug on campus?

All I did was rob and mug on campus

Sliced, rolled dice, got shiest on campus

Had the toast, got bad, paid the price on campus

Forgot about ball, I was done, dude

Now I’m in county in an orange jumpsuit, middle of Texas

But it’s still fun to wonder just how good in-his-prime Cameron Giles was on the court. He could keep up with some of the city’s best, yeah, but did Cam have real game? Like, could’ve-gone-on-to-become-special game?

The answer comes from the great Tom Konchalski, a Queens-based high school scout with a razor-sharp memory who remembers watching Giles play regularly in the early 90s. “He was a defender and he knew his role on the team,” Konchalski says. “Especially when he played Riverside, because they always had stars. They were loaded with guys that would end up in the NBA or come close to that. But he was a good basketball player—typical inner-city, tough, gritty-but-focused guard.”

At about 6-1, Cam was an Allen Iverson-esque scoring point. “He was quick,” says Charlie Jackson, who coached Manhattan Center Cam’s senior year. “Fiery.”

“He was always driving to the basket—that was his main thing,” says streetball star Rafer Alston, a Queens native who at various points played both with and against Giles. “You couldn’t really stop him from going to the basket. He wasn’t gonna shoot no jump shot. The good thing about him was he was tough, and he wouldn’t back down from any competition.”

To make a legitimate name for yourself in the New York City high school basketball world when Cam’ron did so was no easy feat, either. This was a time when the NYC hoops scene was on fire—gyms were packed, with NY Times and Newsday writers always somewhere in attendance. And Cam faced up against all of the city’s best talent. “Rafer, Steph [Marbury]—I busted they ass,” he says with a smile. “I didn’t have the hype they had, that’s why I took pleasure in killing them all the time. I’m not just saying this because I’m talking to you—I really used to kill them for fun.”

Gotta hear both sides! “Cam had some game, but he wasn’t on [Marbury and my] level,” Alston says with a chuckle after I read him the aforementioned quote. “He wasn’t elite. There were a lot of guys that played with us, but our games, we were, like, too deep into basketball. Our games—Stephon and myself—we would eat, sleep, shit basketball. That was just what we did. Each year, our games just kept getting better and better. [Cam’s game] never got better like Stephon’s and my game.”

And yet, we still have to ask: Had he handled that first-round loss a little better, or not gotten hurt and/or arrested upon arriving to a small JuCo in Texas, could the NBA have one day been in the cards?

“I don’t know about that,” Konchalski says.

“I did think he was gonna be a good college ball-player,” Jackson says.

So, yeah: the self-proclaimed loser of Hoosiers was a pretty damn good hooper, even if he probably wasn’t headed for a fat NBA contract. But whatever, man. Those platinum and gold plaques certainly sufficed just fine.

Adam Figman is a Senior Editor at SLAM. Follow him on Twitter @afigman.